FGF E-Package

The Confederate Lawyer

August 12, 2009

Three Heroic Popes — Part I

by Charles G. Mills

GLEN COVE, NY — The destruction of Western Christian Civilization had its beginnings in the late 15th century in northern Europe. Three centuries later, in approximately 1790, the destructive forces had gained enough momentum to reach the heart of Europe. During the next hundred years, three brave Popes stood firm against the tide of decay. This column will cover the heroic lives of two of them. The third, Pius IX, will appear in my next column.

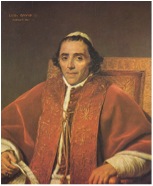

Pius VI (1775-1799)Pius VI (Giovanni Angelico Braschi) was elected Pope in 1775, in large part because he was acceptable to both major factions in the Church. He was a great patron of the arts and established the Vatican Museum.

In 1790, 15 years into his papacy, he faced a major crisis when the members of the revolutionary French government decided that they, not the Pontiff, should have authority over the bishops in France. They abolished 57 dioceses and all archdioceses and claimed the power to appoint all bishops. They forbade bishops from seeking confirmation of their appointment from the Pope and forbade all clergy from appealing to Rome. Moreover, they required that all clergy take an oath of loyalty to the French Constitution. This split the French clergy down the middle: those who were loyal to the Pope refusing to take the oath, and those who went along with the government.

Pius asked King Louis XIV to oppose these anti-Catholic measures, and Pius suspended any priests who took the oath. King Louis XVI, despite attempts to appease the revolutionaries, was soon beheaded. Pius VI protested this brutal execution. Pius VI himself was hated by the revolutionaries, who burned an effigy of him. The Marquis de Sade and Sylvain Marechal included obscene parodies of him in their works.

Napoleon Bonaparte waged a series of wars against the Pope from 1796 to 1798 that ended in the capture of Rome and “unbaptizing” ceremonies in the holy city. When Pius VI refused to renounce his temporal power, Bonaparte tried to destroy the papacy. He took Pius prisoner and moved him further and further north, city by city. Eventually Pius VI died in captivity in 1799. Some historians believe that he was martyred.

Pius VII (1800-1823)

One of Pius VI’s last acts was to require that the conclave to elect his successor be held in Venice, which was still a free republic and where most cardinals were at the time of his death. This frustrated Bonaparte’s plan to prevent a new conclave, and Pius VII (Barnaba Chiaramonti) was elected in 1800. He succeeded in returning to Rome. The following year, Bonaparte entered into a truce with the newly-elected Pope that allowed Bonaparte and Pius VII to coexist in a fragile peace, despite repeated personal insults by Bonaparte. The Pontiff, however, refused to agree with anything that would compromise the rights of the Church, and Bonaparte limited his attacks on the rights of the church.

This tenuous truce ended in 1809 when Bonaparte declared Rome to be part of the French Empire. He began arresting cardinals, and it became clear that he had not abandoned his 1799 plan to destroy the papacy. Despite the presence of hostile French troops in Rome and the arrest of most of the Roman Curia, Pius VII excommunicated Bonaparte and the French Army and circulated copies of the excommunication.

When Bonaparte was defeated and exiled in 1815, Pius VII made a triumphant return to Rome after more than five years of house arrest in France. The Roman people almost unanimously celebrated their liberation from the French. That same year, the Congress of Vienna restored the Papal states and the diplomatic privileges of the papacy.

The Congress of Vienna ushered in a period of relative safety from the anti-Christian violence of the Revolutionaries, but their ideas continued to fester below the surface. An example of this occurred in the early 1820s, when an anti-Catholic revolutionary government took power in Spain. However, that government fell within four years and all its anti-Catholic laws were repealed. Between the late 1840s and the 1870s, revolutionary violence repeatedly broke out, and another heroic pope opposed it He is the subject of my next column.

The Confederate Lawyer archives

The Confederate Lawyer column is copyright © 2009 by Charles G. Mills and the Fitzgerald Griffin Foundation, www.fgfBooks.com. All rights reserved.

Charles G. Mills is the Judge Advocate or general counsel for the New York State American Legion. He has forty years of experience in many trial and appellate courts and has published several articles about the law.

See his biographical sketch and additional columns here.

To sponsor the FGF E-Package, please send a tax-deductible donation to the:

Fitzgerald Griffin Foundation

344 Maple Avenue West, #281

Vienna, VA 22180

1-877-726-0058

publishing@fgfbooks.com

or donate online.

@ 2025 Fitzgerald Griffin Foundation