FGF E-Package

The Reactionary Utopian (classic)

March 19, 2012

The Curse of Beatlemania

A classic by Joe Sobran

fitzgerald griffin foundation

A few weeks ago I wrote some mild criticisms of the Beatles and the sky fell. Angry readers called me “ignorant,” “vicious,” and various other things displaying blindness to my finer qualities. I hadn’t realized there was a militant Beatle Taliban, and I was an infidel. I was lucky to escape a fatwa.

Some of the Beatles’ fans did make civil and reasonable arguments; they defended George Harrison as a guitarist and reminded me that such musical luminaries as Leonard Bernstein and Frank Sinatra had praised them.

But Bernstein was surely over the top when he called Lennon and McCartney the greatest composers of the twentieth century. What about — sticking to pop music — Johnny Mercer, Harold Arlen, Harry Warren, Richard Rodgers, and Frank Loesser? And when Sinatra called Harrison’s “Something” one of the greatest songs of its era, I think it did more credit to his generosity than to his judgment. (Sinatra went to unfortunate lengths to prove he wasn’t an old fogey, as witness his excruciating recording of “Bad, Bad Leroy Brown.”)

It’s not that I hate the Beatles; I’ve always liked them well enough. I used to play their tapes on long drives with my kids, and we all enjoyed them.

What I did hate from the beginning was Beatlemania. It made me uneasy for reasons I didn’t quite understand at the time. The main reason was that the enthusiasm was so synthetic. My generation didn’t discover the Beatles in the normal way; the Beatles were imposed on us by publicists and marketers.

Once upon a time, fame was slowly acquired. A man’s reputation spread gradually, and his good name was so hard-won that he might fight a duel over an insult or a libel. Abraham Lincoln nearly had to cross swords (literally) with a man he had ridiculed in a newspaper.

Even in the world of pop music, a singer used to have to perform for years, making contact with small audiences from town to town, before he “hit the big time.” He had to earn appreciation. It was hard work, but local fame necessarily preceded national fame.

With the Beatles something new was happening. National fame (at least on this side of the Atlantic) was created instantly. It wasn’t due to their music; it was due to their promoters. Millions of kids allowed themselves to be manipulated into an enthusiasm few of them would have arrived at on their own. Pop music was no longer really “pop” — the result of interaction between music and listener.

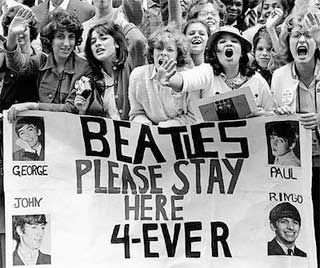

As soon as they got off the plane, the Beatles were mobbed. This was not a phenomenon of musical taste. Their screaming fans wouldn’t even allow them to be heard, weren’t interested in listening.It was weird. I felt a pang of sympathy for the boys, because they obviously wanted to perform; they wanted to be musicians, and their own fans were making it hard. Could they be enjoying that kind of attention, which ruled out any real connection with the audience?

To me it all smacked of the “two- minute hate” in Nineteen Eighty-Four — far more benign, but equally mindless. It wasn’t the Beatles’ fault. Their fans neither knew nor cared who was engineering the mass emotions that swamped the music. Even as a kid, I didn’t want to be part of that, the submergence of the self in the mass.

Since then, what we call “pop” culture has become uncomfortably close to totalitarian politics. Even our aesthetic tastes are increasingly formed by forces of which we know little. It can’t be good for the soul to be subject to so much calculating hype and promotion.

Democracy too has come to mean mass manipulation, with lots of focus groups, demographic studies, and advertising techniques replacing rational persuasion. The individual who prefers to make up his own mind knows he counts for nothing in today’s “democratic process” (eerie phrase!). You have a choice of which mass to join, that’s all. Either way, you’ll make no difference to the outcome.

On the other hand, some people find it thrilling to be part of a stampeding herd, without asking what started the commotion. They should feel right at home in these times.

We live in a world in which the passive and malleable mass has become prior to the individual and the community. Beatlemania didn’t originate this condition, but in its own way it was an intimation.

The Reactionary Utopian archives

Copyright © 2012 by the Fitzgerald Griffin Foundation. All rights reserved. This column was published originally by Griffin Internet Syndicate on December 27, 2001.

Joe Sobran was an author and a syndicated columnist. See bio and archives of some of his columns.

Watch Sobran's last TV appearance on YouTube.

Learn how to get a tape of his last speech during the FGF Tribute to Joe Sobran in December 2009.

To subscribe to or renew the FGF E-Package, or support the writings of Joe Sobran, please send a tax-deductible donation to the:

Fitzgerald Griffin Foundation

344 Maple Avenue West, #281

Vienna, VA 22180

1-877-726-0058

publishing@fgfbooks.com

or subscribe online.

@ 2025 Fitzgerald Griffin Foundation